Everything you need to know about cat rabies vaccines but didn't know who to ask

Which vaccines are less likely to cause the dreaded Feline Injection Site Sarcomas?

Did you know the Rabies vaccine is the only immunization required by law for pets in the United States?

As a cat parent to 2 incorrigible tuxedos, I’m the first to ashamedly admit my ignorance on the topic of feline rabies vaccination. But I suppose it was only a matter of time before I turned my inexhaustible curiosity and penchant for pulling back the veil on all things human health and transgressed into the realm of veterinary medicine.

If you’re a dog parent, it behooves you to read my exhaustive research on this topic for canines here.

Whilst there exist parallels between rabies vaccination for dogs and cats, some things are significantly different. This article is written without the expectation that the reader has a working knowledge of rabies vaccination in dogs, but if you do, understanding cat rabies vaccination becomes a whole lot easier

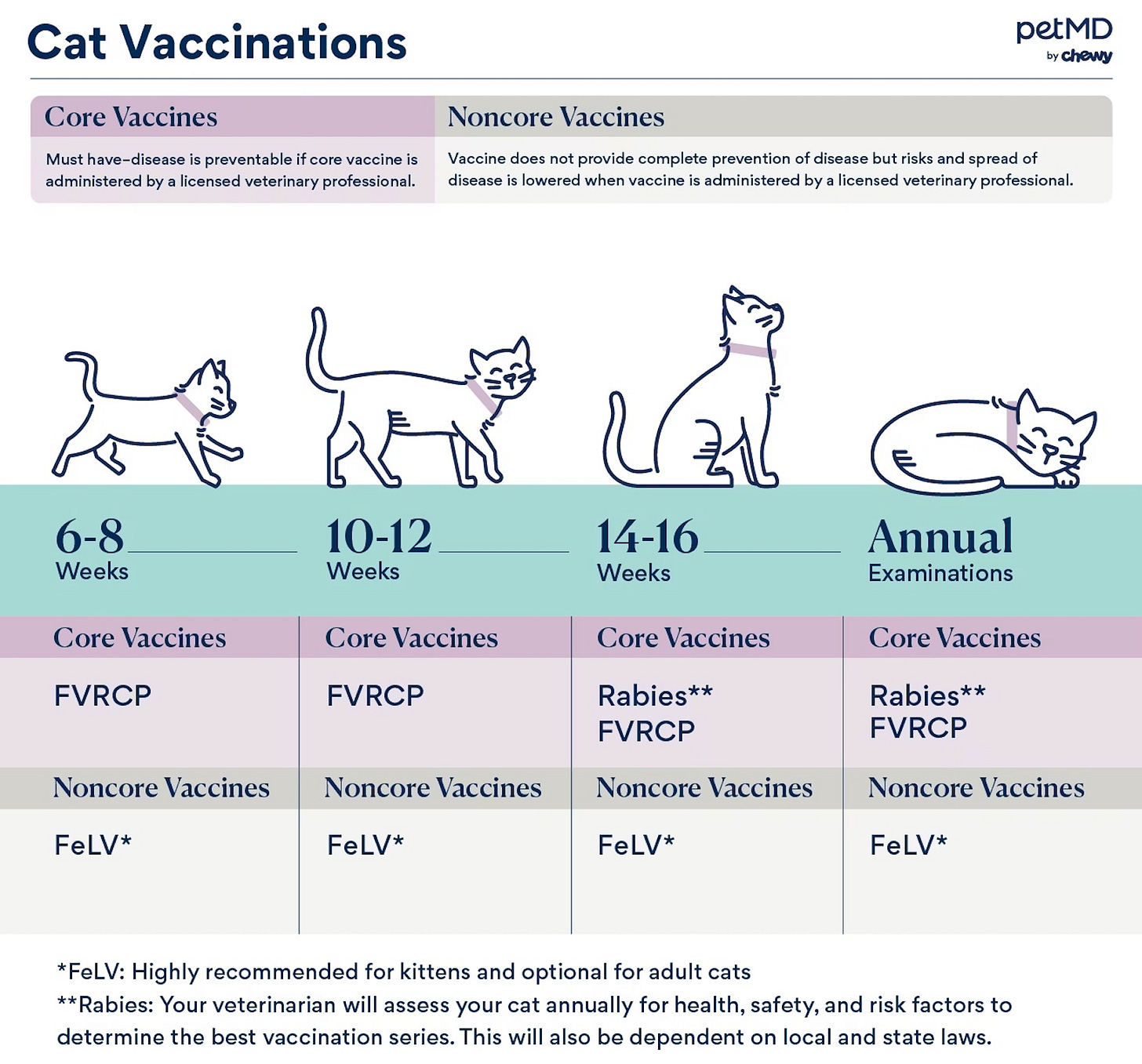

Very much like dogs, Cats typically receive their first rabies vaccine around 12-16 weeks old, followed by a booster a year later, and then boosters every 1-3 years depending on the vaccine type and state regulations.

After the initial series, the frequency of rabies vaccinations can depend on several factors, including:

Type of Vaccine: Some vaccines offer 1-year protection, while others provide 3-year protection.

State Regulations: Local and state laws may dictate the frequency of rabies vaccinations.

According to the CDC, an animal is only considered immunized 28 days after initial vaccination. Animals with any vaccination history are considered vaccinated immediately after a booster, even if the animal was overdue for its vaccine.

Vaccine schedules vary by product and state; local laws may also influence the timing for rabies vaccine schedules. Cats should not be vaccinated before 3 months (12 weeks) of age, as the response to vaccination is not as strong in young animals.

As with dogs, some states allow exemptions to mandatory feline rabies vaccination while others don’t. For a complete list of individual state laws, click on the picture below to be redirected to the Michigan state University animal Center.

Type of vaccines and their association with Feline injection site sarcomas

Prior to discussing duration (i.e. one-year vs three-year) a critically important question that needs to be answered is what type of vaccine will be entering your animal’s body.

A killed virus vaccine consists of virus particles, bacteria, or other pathogens that are grown in culture and then killed using heat or formaldehyde.

Modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines contain bacteria or a virus that has been modified. This means they’ve lost their disease-causing ability.

The other main constituent in vaccines is the adjuvant. An adjuvant is a substance that acts to accelerate, prolong, or enhance immune responses when used in combination with specific viruses or bacteria in vaccines.

Some of the adjuvants used in veterinary vaccines are aluminum salts (alum), oil emulsions, saponins, liposomes, microparticles, derivatized polysaccharides, cytokines, and a wide variety of bacterial derivatives.

Adjuvants are foreign compounds injected animals’ bodies to stimulate an immune response. Reactions to these adjuvants can range from reduced activity and food intake one day post-vaccine to life-threatening reactions that occur within 30 seconds of vaccine administration. Major changes to your four-legged’s health might also include occasional reactions, for example, debilitating allergies or autoimmune problems like Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA), which may show up 1- 5 months post vaccination.

The most dreaded side effect of rabies vaccines is Feline injection site sarcomas or FISS (also known as vaccine-associated sarcomas)

Although the exact mechanism is unknown, inflammation induced by vaccines and adjuvants is thought to play critical role in tumor development. Injection site sarcomas are extremely locally invasive. Multimodal therapy, incorporating combinations of surgery, radiation therapy, and sometimes chemotherapy or immunotherapy, is required. Unfortunately, tumor recurrences are common even with aggressive treatment, and many cats with FISS ultimately succumb to this devastating disease.

Tumors linked to vaccine administration are high-grade sarcomas.

Untreated, affected cats will die from complications associated with the tumor.

Time from vaccination to tumor development is typically between 3 months and 4 years. A smaller number of tumors develop 5 or more years after vaccine administration.

Radical excision (3- to 5-cm margins and 2 muscle planes deep), along with radiation therapy, is recommended for tumors arising in skin over the thorax or abdomen. Limb amputation is recommended for tumors at injection sites on a limb.

Despite aggressive surgery, recurrence rates up to 50% are reported.

Local recurrence is common when simple excision of the tumor is attempted; 86% of recurrences develop within 6 months.

Pulmonary metastasis occurs in 21% of cats diagnosed with grade 3 tumors.

(Personal note: my last cat, who was also a tuxedo, died of pulmonary metastatic disease from an unknown primary source. Now I wonder if the primary was an FISS that we missed.)

In 1993, an epidemiologic study involving 345 cats with fibrosarcoma showed that vaccination with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and rabies virus vaccines could lead to tumorigenesis at the injection site, particularly when vaccination was repeatedly administered at the same site. At the time the study was conducted, all FeLV and rabies virus vaccines licensed for cats in the U.S. were inactivated, adjuvanted products. This raised concerns that chronic inflammation caused by adjuvant-containing vaccines, rather than one particular vaccine brand, played a role in the pathogenesis of these tumors.

In another study, pathologists from the University of Pennsylvania reported an alarming 61% increase in the number of injection-site fibrosarcomas among feline biopsy accessions from 1987 to 1991. This increase was epidemiologically linked to the enactment of a mandatory 1987 rabies vaccination law for pet cats residing in Pennsylvania. They found aluminum in the macrophages surrounding three tumors by electron probes.

Because of adverse reactions related to adjuvants, especially in cats, a new recombinant vaccine was created. The recombinant vaccine is created by taking small pieces of DNA from the specific virus and inserting the DNA into the Canarypox virus, which is a separate virus that does not cause disease. Recombinant vaccines do not require adjuvants to stimulate the immune system. Because the recombinant viruses are alive, they naturally stimulate the body’s immune system to create immunity to the disease virus, such as rabies.

A word of caution here: a 2012 retrospective analysis of cats with soft tissue sarcomas showed that probabilistically speaking FISS was far less likely to be caused by recombinant vaccine. However, the authors concluded that no specific type of rabies vaccine was completely risk free because confounding factors in the study did not allow such a conclusion.

With this explanation out of the way, here is a table of all currently available feline vaccines licensed in the United States:

As you can see (highlighted for your convenience), there are only two non-adjuvant containing vaccines (PureVax), both recombinant, and both made by the same company (Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health), licensed for one and three year durations. Everything else contains an adjuvant.

Based on what we know, recombinant non-adjuvanted rabies vaccines are the safest choice for cats.

So what is the difference between the one and three year PureVax vaccines?

Answer: Cost. The three year costs 2-3 times as much as the one year rabies vaccine.

As for the canine rabies vaccine, there do not appear to be any differences in volume (both are 0.5 ml) or disease agent administered between the one and three year Purevax vaccines. Besides cost the only difference appears to be in how they are labeled and and duration they are licensed for (I think). Here is a snapshot of the Purevax European Union Package insert. If any veterinarians are reading this and would like to disabuse me of my presumption, please feel free to do so in the comments (please provide links)

The very first recombinant vaccine Merial/Boehringer Ingelheim created and tested was the one-year Purevax Feline Rabies vaccine. Many veterinarians began to utilize this vaccine instead of the adjuvanted vaccines. For a long time, this was the only recombinant option for cats, so when a vet said, “I recommend the one-year vaccine for your cat,” it was as opposed to the only other available option: a three-year adjuvanted rabies vaccine. As of 2014, there is an approved three-year Purevax (recombinant) Feline Rabies vaccine. However, many veterinarians continue to use the one-year Purevax vaccine, since the cost of the three-year Purevax vaccine is three times the cost of the one-year vaccine.

If you have the option to give your cat a three-year Purevax (recombinant) Feline Rabies vaccine, that appears to be the safest choice. However, do not assume that your cat will automatically receive the three year recombinant vaccine.

What do the guidelines say?

As in the case of vaccination for your canine friends, the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) is analogous to the CDC and ACIP in humans and promulgates animal vaccination guidelines that are followed by veterinarians.

These guidelines conveniently sidestep the issue of recommending a specific type of feline rabies vaccine by pleading insufficient evidence exists to do so: “The Task Force believes that there is currently insufficient research to justify recommending a single vaccine type. Since injection site sarcomas are a risk, the Task Force recommends vaccination in the lower distal limbs to facilitate clean margins if surgical amputation is required.” They do, however, refer to the evidence that shows non-adjuvanted vaccines may be safer but call the evidence “tenuous”

These recommendations and conclusions must be taken with a grain of salt (or more like a bag) because, as with canine recommendations, the whole enterprise is funded by the very pharmaceutical companies that manufacture these vaccines and recommending one product over the other would jeopardize their gravy train.

The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) however goes one step further and makes useful recommendations including the use of non-adjuvanted vaccines over those that contain adjuvants.

Subcutaneous injections should not be made into the interscapular furrow of cats.

Vaccines should not be injected intramuscularly if subcutaneous injection is a legal alternative.

Vaccines should be administered into different anatomical sites on each occasion of use.

It is not clear that any kinds of vaccine are completely safe.

Any risk of FISS is far outweighed by the benefits of protective immunity conferred by vaccines.

The VGG recommends that use of non-adjuvanted feline vaccines should be favored over adjuvanted vaccines in countries where FISS is known to occur and where alternative vaccine choices are available. If no acceptable alternatives are available, it is much preferable to vaccinate with an adjuvanted product than not at all.

The anatomical site of injections should be recorded in the patient's medical record or on the vaccination card, including by use of a diagram, indicating which products were administered on any one occasion. The sites should be “rotated” on each occasion. Alternatively, a practice might develop a group policy that all feline vaccinations are administered to a specific site during one calendar year and this site is then changed for the following year.

Conclusion

Unlike in canines, there are no long-term (greater than three year) rabies virus challenge studies showing longer duration of vaccine protection in cats. If there are, I couldn’t find them and would be very interested if someone reading this points me in the proper direction.

Based upon the evidence, the two recombinant non-adjuvanted feline rabies vaccines—the one and three year Purevax—appear to be safer than those containing adjuvant and should be preferred.

Do not automatically assume that your cat will receive a three year non-adjuvanted vaccine. Hopefully this article has armed you with enough facts to make informed decisions and ask important questions. As always, I remain interested in your thoughts and comments and thank you for reading my research.

At site of injection bump/lump will go away in 3 - 6 months if you leave it alone and avoid treatment.

No vaccine has ever been necessary or safe, and definitely NOT effective. Illnesses & diseases are not THINGS outside of a body. They are a manifestation, a condition, whose cause can be many possible things but are absolutely not microbial.

Ask me about it. Ask me to walk you through it. I'll be happy to talk about it here in the comments or by email or by ZOOM.

There are NO viruses. Never have been. There are NO pathogenic bacteria. They lied to us and preyed upon our primal fears about health just to sell treatments.

Ask me about it. Don't just shake your head and dismiss a dissident of the Establishment Narrative. The Establishment calls dissidents "conspiracy theorists". Are you a tool of the Establishment? Well you are if you spread their disinformation and lies. Yes, sir.

Moxie, 2006-2019, the cat of my heart, started on a downward health spiral after I got her “up to date” on her vaccinations. I loved her a lot.