Dystopia now: The rise of the machines and the de-evolution of human beings

Chapter 1: The jaw dropping explosion in rates of Myopia and blindness linked to computer screen exposure

The man-vs-machine battle was lost almost a decade ago, but we were too busy eyeballs deep in our electronic devices to sit up and take notice. If that sounds like hyperbole consider that by 2014 there were officially more mobile devices than humans on planet earth. To add to the nesting doll of horror, these devices are multiplying 5 times faster than us and getting smarter at speeds that will surpass our intelligence in the not too distant future. Computing power increased an astounding 1 trillion fold from 1965 to 2015 and this exponential rise shows no signs of abating.

It is as if we’re destined to fulfill the movie “Matrix” as a work of prophecy rather than fantasy. While devices evolve more human qualities, humans are devolving back into the gurgling primordial ooze from whence we came. We are slower, fatter, sicker, blinder, more addicted, more anxious, more unhappy and on path to being useful only as human battery cells powering the machines. The more connected we get, the more disconnected we become. What’s more, our pandemic policy that increased reliance on computers and consequently screen time was akin to putting a jet pack on a car hurtling at breakneck speed towards the cliff of self-destruction.

This the first installment in a series of essays on the de-evolution of humans via digitization and describes the frightening epidemic of nearsightedness and associated eye disorders linked to computer screen exposure. Please take a minute to support my work by subscribing and sharing.

Digital Blindness: The Myopia Boom

Excessive screen time is literally reshaping our eyes. Myopia or nearsightedness is when close-up objects look clear but distant objects are blurry. For instance, you can read a map clearly but have trouble seeing well enough to drive a car.

Rates of Myopia are increasing at an alarming clip. It is estimated that around 30% of the world is currently myopic. That number will reach a jaw-dropping 50% by the year 2050. That’s a staggering 5 billion people with eye disease caused by staring at their computer screens. Researchers have christened this epidemic the “Myopia Boom” and they paint a scary picture. We’re currently on track to having:

Almost 5 billion myopes by 2050

Almost 1 billion high myopes by 2050

Myopia is set to become a leading cause of permanent blindness worldwide

Recent studies indicate that myopic macular degeneration is now a serious eye condition and one of the major causes of permanent blindness in Rotterdam, Copenhagen, China, Chinese Taipei, and Japan. Below is a snapshot of the rate of myopia seen in children.

The rest of the world has not fared a whole lot better. Myopia now affects around half of young adults in the United States and Europe — double the prevalence of half a century ago. By some estimates, 40% of the world's population — 3.2 billion people — could be affected by short-sightedness by the end of this decade.

What we’re talking about now isn’t merely a cosmetic inconvenience easily corrected by glasses, contact lenses or surgery. The elongation of the eyeball that occurs in myopia increases the risk of retinal detachment, cataracts, glaucoma and even blindness. Because the eye grows throughout childhood, myopia generally develops in school-age children and adolescents. About one-fifth of university-aged people in East Asia now have this extreme form of myopia, and half of them are expected to develop irreversible vision loss.

What is causing it?

The long-held belief that myopia was purely genetic was challenged by a 1969 study of Inuit people on the northern tip of Alaska whose lifestyle was changing. Of adults who had grown up in isolated communities, only 2 of 131 had myopic eyes. But more than half of their children and grandchildren had the condition. Genetic changes happen too slowly to explain this rapid change. Rather, there had to be environmental factors associated with modernization and urbanization to explain this startling generational difference.

Originally, the rise in myopia mirrored the amount of time children spend doing bookwork as part of their school curriculum. There is a strong association between measures of education and the prevalence of myopia. In the 1990s, for example, researchers found that teenage boys in Israel who attended schools known as Yeshivas (where they spent their days studying religious texts) had much higher rates of myopia than did students who spent less time at their books.

Replacing books with screens has accelerated this process by exponential orders of magnitude. School work is done using computer screens, homework is done using computer screens, and as if that wasn’t bad enough, most leisure involves computer screens and handheld devices. According to one report, the average 15-year-old in Shanghai spends 14 hours per week on homework, compared with 5 hours in the United Kingdom and 6 hours in the United States.

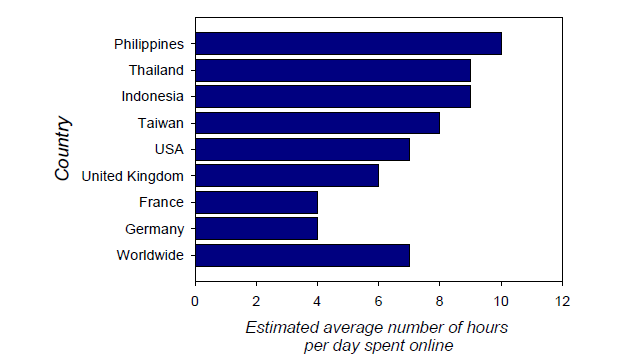

According to a recent dataset from 2019, the worldwide average on-screen time for individuals between 16-64 years of age was estimated to be 7 hours per day.

A 2017 estimate is even more heart stopping. Children between 0 to 2 years of age were spending 2 hours on 20 minutes per day looking at screens, and that number doubled to 4 hours and 30 minutes for children between 8 and 12 years of age.

Can it be fixed? Can we see the light?

Once you dive deeper, things begin to get more interesting. When researchers started looking at specific behaviors including books read per week, or time spent starring at screens, the correlation with myopia was not consistent or linear. However there was another surprising factor that began to emerge.

Donald Mutti and his colleagues at the Ohio State University College of Optometry in Columbus reported the results of a study that tracked more than 500 eight- and nine-year-old Californians who started out with healthy vision. After five years, one in five children had developed myopia. To their own surprise, the only environmental factor strongly associated with risk of developing myopia was time spent outdoors. When controlling for other variables, children who spent less time outside were at greater risk of developing myopia.

Kathryn Rose and her colleagues reached similar conclusions in their Australian study of more than 4,000 Sydney school children. However, they went one step further. They found that time engaged in indoor sports had no protective association, but curiously time spent outdoors did. And it didn’t matter whether children actually played sports, attended picnics or simply read on the beach. Children who spent more time outside were not necessarily spending less time with books, screens and close work but seemed to be less at risk for developing myopia. What seemed to matter most was the eye's exposure to bright light.

Whilst thinking that bright light is a cure-all panacea for our digital blindness is gross oversimplification bordering on wishful thinking, it still deserves consideration. Animal experiments in chicks, tree shrews and rhesus monkeys support the idea that light is protective against experimentally induced myopia. The leading hypothesis is that light stimulates the release of dopamine in the retina, and this neurotransmitter in turn blocks the elongation of the eye during development.

Retinal dopamine is normally produced on a diurnal cycle — levels climb during daytime wakefulness and ebb at nighttime. Higher dopamine signals the eye to switch from rod-based, nighttime vision to cone-based, daytime vision. Researchers suspect that under dim (typically indoor) lighting, this cycle is disrupted and has adverse consequences for eye growth. Dopamine appears to be the master hormone in understanding a lot of what computer screens do to our neural circuitry, and indeed is the underlying theme in many disorders associated with diseases emerging as a consequence of excessive computer use, as you will see in subsequent chapters in this series.

Myopia researchers at the Australian National University in Canberra estimate that children need to spend around three hours per day under light levels of at least 10,000 lux to be protected against myopia. This is about the level experienced by someone under a shady tree, wearing sunglasses, on a bright summer day. (An overcast day can provide less than 10,000 lux and a well-lit office or classroom is usually no more than 500 lux.) Three or more hours of daily outdoor time is already the norm for children in Australia, where only around 30% of 17-year-olds are myopic. But in many parts of the world — including the United States, Europe and East Asia — children are often outside for only one or two hours.

Teachers at a school in Southern Taiwan were asked to send children outside for all 80 minutes of their daily break time instead of giving them the choice to stay inside. After one year, doctors had diagnosed myopia in 8% of the children, compared with 18% at a nearby school.

While these findings aren’t nearly as conclusive as we’d like and further research continues, two things are pretty clear:

There is an epidemic of Myopia and associated eye diseases that parallels the increase in screen time over the last decade. This is gargantuan health crisis in the making with little call to action from public health authorities, especially when you consider that children and young people with most of their lives ahead of them are the most affected.

Light, including its luminance and wavelength, directs the direction of eye growth and dopamine synthesis. The available research seems to agree that increasing the time spent outdoors is an effective measure for preventing myopia.

Contemporary research is focusing on blue and violet light exposure as a means of controlling myopia whereas red light exposure appears to have potential to improve choroidal blood perfusion in the eye. As always, there will be heated debate, contradictory research findings and the usual hand waving from self appointed experts that will confuse and confound. Science is messy.

What absolute joy then that the age old tried and trusted advice of our grandparents and ancients to go outside, get fresh air, touch the grass and feel sunlight on your face is even more relevant today than it ever was. The thing that distinguishes us from machines might be the thing that saves us in the end.

I hope you found this essay illuminating (pun intended). Please take a minute to sign up so you don’t miss the next installment in this series. And be sure to share it with people you care about.

Kudos to you for tackling this subject. Having been myopic as a child, developing early onset of floaters and cataracts long before usual, I discovered there is already a lot outside of the conventional medical world about vision improvement and eye health. Engaging in this has helped me, a high-risk eye disease patient, avoid seeing an ophthalmologist for well over a decade - which might seem foolish given the preciousness of eyesight. I’m really glad to see people in the medical/health sector, such as yourself, start to look beyond existing understanding.

Another very interesting essay. I always learn from you. I’ve always been an avid reader & developed myopia in early 20s. My daughter also avid reader since 3 yo (I know, right) developed myopia in 4th grade. When e-readers came out I switched for convenience but during Covid I went back to actual books again-there’s nothing like the smell of fresh ink & the feel of holding one & turning actual pages. Still spend too much screen time.

I wonder what impact diet/nutrition has on eye health. This year I’ve focused on metabolic health by eliminating most processed foods, seed oils, grains, & sugar not sure impact on eyes but I sure feel better. It would be interesting to study.